Deciphering the Kristen Stewart Phenomenon

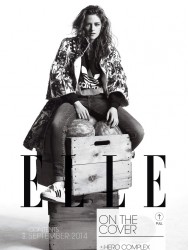

At once the ultimate tough girl and the vulnerable everygirl, Kristen Stewart has been bringing emotional, undeniably real characters to the big screen for more than a decade. She has millions of fans and a slew of new projects big and small, but the actress's most impressive feat to date? Tuning out all that noise.

Kristen Stewart is famous for—no, scratch that. Famous is too dinky a word to describe what Kristen Stewart is at this moment in America's cultural history. Kristen Stewart is a phenomenon for playing the girl in the Twilight movies, only, of course, she was really playing the boy. That's the secret of the franchise's appeal: It's a rehash of that tired old mothball-reeking, done-to-death, oh-Jesus-not-again Romeo and Juliet star-crossed-lovers redux, except—and here's what makes the material so fresh, gives it its kinky kick—he's Juliet and she's Romeo. Robert Pattinson's Edward Cullen—gorgeous, moody, high-strung, faintly anemic because he's a bloodsucker who refuses to suck human blood, his principles as lofty as his cheekbones—is the object of desire, and he is photographed as adoringly and fetishistically as Dietrich in any of the von Sternberg pictures. He is, as well, the beast that's also the beauty, one in serious distress, cursed to be 17 forever and mateless, a Prince of Darkness without a Princess, not to mention a prom king without a queen. It's Stewart's Bella Swan, quiet and strong and full of purpose, who brings an end to his loneliness by surmounting the obstacles, both physical and metaphysical, in their path, converting to vampirism so it's possible for them to unite for all eternity. (Those feminist-watchdog types, sensitive noses aquiver for the slightest whiff of peepees-are-better-than-weewees, decrying Bella and, by extension, Stewart as some sort of self-sacrificing, female-chump retro case, have, as usual, got it wrong. If Bella falls into a gender stereotype, it's not Clinging Vine; it's White Knight. She just has enough grace—gallantry, too—never to throw in her true love's face the fact that she's the one rescuing him.)

While we're on the subject of secret appeal, here's Stewart's: She's a lovely looking girl, possessed of both soulful intelligence and depth of feeling, yet in the blink of an eye she can turn into a hot young roughneck ready for action, for kicks, for anything. The former persona, delicate without being weak, is why she's so affecting in movies such as Into the Wild (2007) and Adventureland (2009) and On the Road (2012), the perfect match for Emile Hirsch's doomed wanderer and Jesse Eisenberg's lovelorn egghead and Garrett Hedlund and Sam Riley's word-drunk beatniks who only want to go go go even if it's to no place in particular or just into one another's beds. Which isn't to say that these numbskull boys always get it, can see what's smack-dab in front of them. (All Stewart has to do is look at Hirsch's Chris McCandless in a hurt and wondering way, and it's obvious he should bag that trip to the Alaskan wilderness he can't shut up about and stay with her in her parents' rig in Imperial Valley.) The latter persona, so assured it borders on arrogant, borders on macho, is why she's able to pull off the low-lidded stares of pure lust she directs at Dakota Fanning's saucer-eyed cutie-pie in The Runaways (2010). It's why she's able to pull off, too, the trick of becoming Joan Jett, the woman who proved you don't need a cock to rock, you just need to strap on that guitar, strut that stuff, and create a sound that leaps right out of the jukebox—fast, urgent, full of vitality and aggression and rollicking good times.

Not that Stewart is the first young actress to discover what a turn-on gender ambiguity can be for an audience. Angelina Jolie, for God's sake! When Jolie went from nowhere to everywhere seemingly overnight in the late '90s, she wasn't only the hottest girl the world had ever seen, she was the hottest guy, too, with a swagger to her step, a curl to her lip, a bad to her bone: the most babelicious babe and the studliest stud, all in one. But in the past few years, it's as if she's so sexy her sexiness has come full circle. She appears complete unto herself, doesn't need another person. Her early vulnerability (the look in her eye was as often wounded as it was wounding) is something she's outgrown. Stewart, though, has still got it, and it's what makes her one of the most romantic—and exciting—female presences on the screen today.

Okay, so that's Kristen Stewart, the movie star and sex symbol.

I get together with Kristen Stewart, the person, at the tail end of a Monday morning in June in Culver City. We're meeting at the studio of artist Ed Ruscha. I'm from the East Coast, and tales of L.A. traffic have me good and freaked, so I arrive more than half an hour early. When Stewart shows up, on time to the minute, I'm being given a tour of a men's room filled with Marilyn Monroe tchotchkes; two dogs, both named Lola; and torn-out pictures of Jesus by Ruscha's brother, Paul. Stewart calls my cell to tell me she's outside. I open the door.

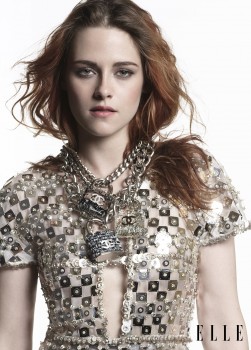

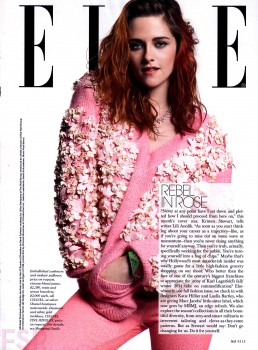

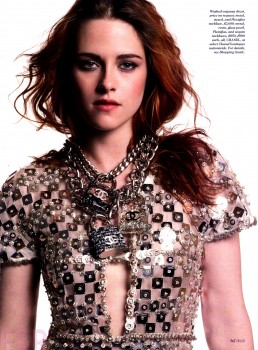

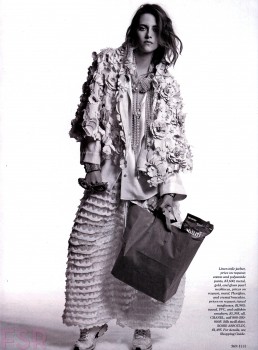

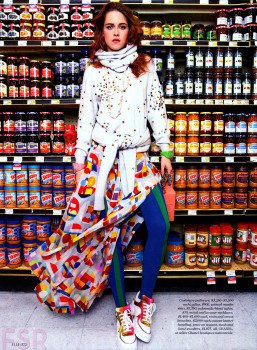

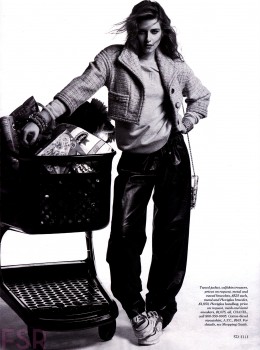

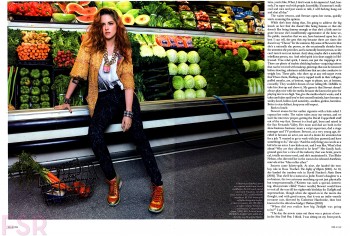

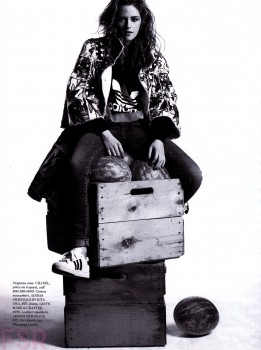

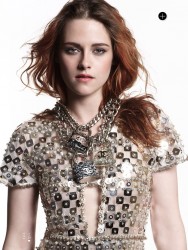

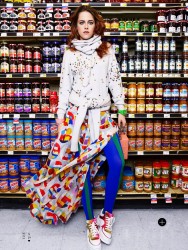

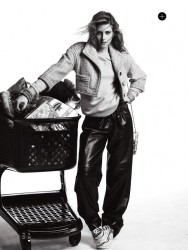

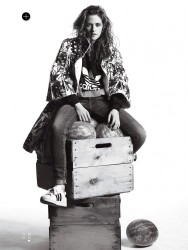

The girl on the other side might have made an eerily convincing young Joan Jett—says the real Joan, "Kristen studied me. Watched me talk, sing, breathe, just be. It got to the point where the two of us stood together and people couldn't tell us apart"—but it's a young Elvis Presley she's a dead ringer for: same almond-shape eyes (her vivid blue-green ones were dulled to a mud brown for Twilight), outlined in black, the lids heavy, hooded; same complexion, an undead shade of white, and without a mark, as poreless as marble; same mouth, narrow but full, made to sneer. She's rock 'n' roll skinny in tight jeans, scuffed Vans, a V-neck T-shirt, a pair of sunglasses dangling from the collar, hair long and tangled and dyed a brassy red, the roots dark. The look, pure Southern California street-punk guttersnipe, is very anti-glamour-puss. But she can downplay her natural assets only so much. Do I even need to tell you that she's very, very pretty? And though now 24, she could pass for much younger—a kid, fresh out of high school.

Stewart and I shake hands, and I introduce her around. Her manner is bashful, skittish, but she also seems eager to connect. Not just with Ruscha, who entered the room at almost the exact moment she did, but with Paul and Ruscha's assistant, Susan, and both dogs. With me, as well. Ruscha leads us into the body of the studio, which is enormous, originally built by Howard Hughes to manufacture airplane engines. At 76, he's still handsome, lean and suntanned, with a thick head of gray hair and lady-killer blue eyes. (His past girlfriends have included actress Samantha Eggar and model Lauren Hutton.) He looks less like an artist than like an old-time star of Hollywood westerns—Gary Cooper, maybe—only paint-spattered. Sounds like a western star too, not using many words when he talks, the words he does use coming out in a soft Oklahoma drawl. An ex-squeeze once called him "the king of shit-kicker cool." The title still fits.

The rapport between Ruscha and Stewart is natural and instant. He knows she appeared in Walter Salles' adaptation of On the Road, playing Marylou, Dean Moriarty's "beautiful little sharp chick," not a day over sweet 16, first seen naked, save for a pair of white cotton undies, rolling the perfect joint. He brings out a fine-arts edition of Kerouac's novel—one of Stewart's favorites—that he created a few years ago, photographs illustrating the text. As he turns the pages, Stewart calls out the names of the objects and places pictured: now-defunct brands of beer and automobiles, a pack of filterless cigarettes—"We smoked so many of those on the shoot we thought we were going to die!"—a plate of apple pie à la mode, so-lonesome-I-could-cry stretches of Arizona highway, Mexican whorehouses. She does this not in a show-offy way but with the pleasure of recognition, because she's seeing something that moves or excites her.

After Ruscha closes On the Road, he and Stewart continue to shoot the breeze, pushing remarks easily back and forth. They're bonding over a mutual love of light leaks in photos when I'm forced to break in because of a 12:15 lunch reservation and a promise I made to Stewart's publicist not to be too much of a little piggy with her time. Ruscha pulls out two copies of his book Porch Crop, inscribes one to her, one to me, and, cowboy gracious, walks us to the door.

Stewart and I take her black Mini Cooper, actually her mom's, to a restaurant a few blocks away. Before we walk inside, though, she ducks into a little nook/alleyway for a cigarette, which she smokes nervous-fast. Once we're at the hostess's station, I understand her momentary spasm of anxiety. Her head is bowed, posture turtled—she's practically willing herself into invisibility—and still people's eyes are drawn to her like iron filings to a magnet. Everybody stares. I mean, everybody. Even the people who look like they're not staring are staring. It's at that moment I realize—re-realize, I should say, since I knew it before meeting her but forgot after, so low-key does she seem, so unassuming, so, well, normal—just how major league a celebrity she is. Realize also that she must live much of her life at the mercy of strangers. For example, if just one of our fellow patrons decides to blow her cover by calling a news outlet (hey, this is L.A., people here probably have the scandal rags on speed dial) or tweeting that Oh Em Gee KStew is @ Akasha on Culver Blvd!!!, we'd have to go. Go hungry too.

The hostess leads us to a discreet table at the restaurant's rear. A waiter drops off menus and water. Stewart takes the chair facing the wall, giving her back to the room. Once it's clear we're alone and settled and no one's going to bug us, she visibly relaxes, pushing her hair out of her face and releasing the breath she must have been holding since we stepped through the doors.

For a minute or two we discuss the extreme weirdness of being her.

"So, basically, you can never look at people," I say.

"I'm obsessed with that. I'm always like, I can't look. Literally, most times, I would be staring at these girls [tilts her head to indicate which ones], but I haven't even glanced over there."

"Can't risk eye contact with strangers, right?"

"Right. Because then you're letting them in. But at the same time, you're like, What, I don't want to let anyone in? And, honestly, I'm super real with people. Incredibly. If someone's really cool and nice and just wants to talk, I will fucking hang out and chat all day."

The waiter returns, and Stewart opens her menu, quickly starts scanning the options.

While she's busy doing that, I'm going to address the big knock on her: that she doesn't like being famous or that she doesn't like being famous enough or that she's a little snot ingrate because she's insufficiently appreciative of the fame we, the public, mensches that we are, have bestowed upon her. As best I can tell, she gets this rep because there are times she doesn't say "Cheese" for the cameras. My sense of Stewart is that she's a naturally shy person, so she occasionally shrinks from the attention she provokes, and a naturally honest person, so she can't turn it on in an instant. And, okay, maybe she's a naturally rebellious person, too. And rebel spirit is in short supply in Hollywood. True rebel spirit, I mean, not just the trappings of it. There are plenty of starlets shticking badass—acquiring tattoos that can be covered with makeup, piercings that can be removed before shooting, substance addictions that are also conducive to weight loss. These girls, who show up at any red-carpet event that'll have them, flashing every capped tooth in their collagen-puffed mouths, are, at bottom, eager to please, are, at bottom, cowardly. They wouldn't dream of ever telling Mr. DeMille to take his close-up and shove it. My guess is that Stewart doesn't always play nice with the media because she knows the price for playing nice is too high. You give the media what it wants, and it takes and takes until you've lost yourself entirely, have become a smiley-faced, hollow-eyed nonentity—soulless, gutless, harmless. Better to stay defiant, keep your self-respect.

Stewart atones for her earlier cigarette with a kale salad. I copycat her order. The waiter takes away our menus, and we start the interview proper, getting the David Copperfield stuff out of the way first. Stewart is a local girl, born and raised in the San Fernando Valley. Her mom and dad are both in the show-business business: mom a script supervisor, dad a stage manager and TV producer. Stewart, at a very young age, decided to become an actor, not out of a desire for attention but for a job. "I wanted to go to work with [my parents] and have something to do," she says. "And the only thing you can do as a kid is be an actor. I saw kids on set, and I was like, What's that about? Why are they allowed to be here?" Her family background gave her a view of the industry that was brisk, practical, totally un-starry-eyed, and she's maintained it. Tim Blake Nelson, who directed her in the soon-to-be-released Anesthesia, marvels at her "blue-collar ethos."

Success came lickety-split. At nine, she landed the tomboy role in Rose Troche's The Safety of Objects (2001). At 10, she landed the tomboy role in David Fincher's Panic Room (2002). That she'd be a natural as Jodie Foster's daughter is a no-brainer, the two actresses matching up not just physically but temperamentally. ("Kristen was such a special, interesting, idiosyncratic child," Foster recalls.) Stewart would have to wait all the way till her eighteenth birthday for Twilight and superstardom, though when she signed on to the movie she thought, and with good reason, that it was an indie—mostly no-name cast, directed by Catherine Hardwicke, then best known for the ultra-low-budget Thirteen (2003).

"When did you realize how big Twilight was going to be?" I ask.

"The day the movie came out there was a picture of me—in the New York Post, I think. I was sitting on my front porch, smoking a pipe with my ex-boyfriend and dog. And I was like, Oh shit, well, I have to be aware of that."

She admits she found the sudden fame hard to handle: "I hadn't carved out my spot, and people hadn't gotten used to me yet. It was really fucking hard. I didn't interview well. I was really nervous. People fucking didn't respond that well."

In the past couple years, it's been back to the smaller-scale, more intimate projects Stewart was doing before and during the Twilight saga, with Snow White and the Huntsman as the notable exception. This souped-up, rock-'em-sock-'em retelling of the classic fairy tale enchanted audiences, if not critics, and helped make Stewart the richest of them all. (Forbes named her the highest-paid actress of 2012.)

(...)

Foster must've been gazing into her crystal ball. Stewart managed to hold it together, at least publicly, didn't break down or crack up, and at last the press got bored or lost interest—moved on, in any case. And she seems to have channeled whatever anger or upset she was feeling into her work. She has two movies coming out later this year, Peter Sattler's Camp X-Ray, about the bond that develops between a guard (Stewart) and a detainee (Payman Maadi) at Guantánamo, and Olivier Assayas' Clouds of Sils Maria, about an aging star (Juliette Binoche) and her devoted—too devoted, perhaps?—personal assistant (Stewart), both of which have been knocking them dead at festivals.

I ask Stewart who she's dating these days. Are she and Pattinson secretly back together? Or is she seeing Nicholas Hoult, Hollywood's young hunk du jour? Or has close friend Alicia Cargile become more than that? (In just the past 48 hours I've read gossip items suggesting all three possibilities.) It's none of my beeswax, of course, except that asking none-of-my-beeswax questions is part of my job description. Stewart's polite about it—certainly more polite than I deserve—but lets me know that her private life is precisely that, a stance I find personally admirable if professionally frustrating. She is, however, willing to discuss in abstract terms how a private life is even possible for somebody like her: "I just have to be really conscious. It takes a little bit of the impulsive nature of life out of the equation, but I—"

Stewart's interrupted by a text-message buzz. While she deals with it, I'm going to deal with the other big knock on her: that she has no dramatic range, is the same in every movie, a one-trick pony, basically. And though it's undeniable that the characters she embodies tend to resemble one another—intelligent but nonverbal, troubled, a little withdrawn—they're not identical. Stewart herself is aware of her limitations: "Some people try to do that thing where you craft a character. I cannot be anyone other than who I am. If I can't empathize with something [my character] does, it's a problem. And sometimes I've had directors be like, It's not you, Kristen, it's the character. And I'm like, That's the laziest thing you can possibly say to me. It is me. It's definitely me." My feeling is that Stewart's limitations are, in fact, her strengths. As a performer, she's deceptively simple, so natural is her style, so unforced. To play someone with a personality and consciousness totally unlike her own would be, in her mind, false. Says Jesse Eisenberg, "When we made Adventureland, [Kristen] would cut takes because she felt she was being inauthentic. She was 17!" Often what Stewart's doing appears plain and straight-ahead but is actually nuanced and complex, each of her roles a subtle variation on a common theme: herself. She's an American—Made in California, like the title of that famous Ed Ruscha piece—a West Coaster with a West Coaster's instinctive modesty and hatred of pretension and cool, courtly grace. If she can't make it look easy, she doesn't want to do it at all. Just because she makes it look easy, though, doesn't mean it is, and just because she doesn't put on the airs of an artiste doesn't mean she isn't one. You never see her acting, proof of how very good an actress she is.

Stewart sends off her text, and we keep the conversation going for a few more minutes. Our plates have long since been cleared, though, and she's sipping at the dregs of her coffee, me of my tea. I signal for the check, and we head outside. I sense she wants to smoke but is reluctant to light up because we're walking next to each other and I'm visibly pregnant. Once we say our goodbyes, she reaches for her keys, and I return to the restaurant to ask the hostess to call me a cab. As I wait, I look out the window. There's Stewart, slouched against the hood of her mom's Mini Cooper, squinting into the sun, a cigarette dangling from her lips. After taking a final drag, she lets the flaming butt fall to the pavement and swings her body through the driver's-side door. She starts up the car and enters the heavy flow of traffic on Culver without a pause or hitch. The princess of shit-kicker cool.

At once the ultimate tough girl and the vulnerable everygirl, Kristen Stewart has been bringing emotional, undeniably real characters to the big screen for more than a decade. She has millions of fans and a slew of new projects big and small, but the actress's most impressive feat to date? Tuning out all that noise.

Kristen Stewart is famous for—no, scratch that. Famous is too dinky a word to describe what Kristen Stewart is at this moment in America's cultural history. Kristen Stewart is a phenomenon for playing the girl in the Twilight movies, only, of course, she was really playing the boy. That's the secret of the franchise's appeal: It's a rehash of that tired old mothball-reeking, done-to-death, oh-Jesus-not-again Romeo and Juliet star-crossed-lovers redux, except—and here's what makes the material so fresh, gives it its kinky kick—he's Juliet and she's Romeo. Robert Pattinson's Edward Cullen—gorgeous, moody, high-strung, faintly anemic because he's a bloodsucker who refuses to suck human blood, his principles as lofty as his cheekbones—is the object of desire, and he is photographed as adoringly and fetishistically as Dietrich in any of the von Sternberg pictures. He is, as well, the beast that's also the beauty, one in serious distress, cursed to be 17 forever and mateless, a Prince of Darkness without a Princess, not to mention a prom king without a queen. It's Stewart's Bella Swan, quiet and strong and full of purpose, who brings an end to his loneliness by surmounting the obstacles, both physical and metaphysical, in their path, converting to vampirism so it's possible for them to unite for all eternity. (Those feminist-watchdog types, sensitive noses aquiver for the slightest whiff of peepees-are-better-than-weewees, decrying Bella and, by extension, Stewart as some sort of self-sacrificing, female-chump retro case, have, as usual, got it wrong. If Bella falls into a gender stereotype, it's not Clinging Vine; it's White Knight. She just has enough grace—gallantry, too—never to throw in her true love's face the fact that she's the one rescuing him.)

While we're on the subject of secret appeal, here's Stewart's: She's a lovely looking girl, possessed of both soulful intelligence and depth of feeling, yet in the blink of an eye she can turn into a hot young roughneck ready for action, for kicks, for anything. The former persona, delicate without being weak, is why she's so affecting in movies such as Into the Wild (2007) and Adventureland (2009) and On the Road (2012), the perfect match for Emile Hirsch's doomed wanderer and Jesse Eisenberg's lovelorn egghead and Garrett Hedlund and Sam Riley's word-drunk beatniks who only want to go go go even if it's to no place in particular or just into one another's beds. Which isn't to say that these numbskull boys always get it, can see what's smack-dab in front of them. (All Stewart has to do is look at Hirsch's Chris McCandless in a hurt and wondering way, and it's obvious he should bag that trip to the Alaskan wilderness he can't shut up about and stay with her in her parents' rig in Imperial Valley.) The latter persona, so assured it borders on arrogant, borders on macho, is why she's able to pull off the low-lidded stares of pure lust she directs at Dakota Fanning's saucer-eyed cutie-pie in The Runaways (2010). It's why she's able to pull off, too, the trick of becoming Joan Jett, the woman who proved you don't need a cock to rock, you just need to strap on that guitar, strut that stuff, and create a sound that leaps right out of the jukebox—fast, urgent, full of vitality and aggression and rollicking good times.

Not that Stewart is the first young actress to discover what a turn-on gender ambiguity can be for an audience. Angelina Jolie, for God's sake! When Jolie went from nowhere to everywhere seemingly overnight in the late '90s, she wasn't only the hottest girl the world had ever seen, she was the hottest guy, too, with a swagger to her step, a curl to her lip, a bad to her bone: the most babelicious babe and the studliest stud, all in one. But in the past few years, it's as if she's so sexy her sexiness has come full circle. She appears complete unto herself, doesn't need another person. Her early vulnerability (the look in her eye was as often wounded as it was wounding) is something she's outgrown. Stewart, though, has still got it, and it's what makes her one of the most romantic—and exciting—female presences on the screen today.

Okay, so that's Kristen Stewart, the movie star and sex symbol.

I get together with Kristen Stewart, the person, at the tail end of a Monday morning in June in Culver City. We're meeting at the studio of artist Ed Ruscha. I'm from the East Coast, and tales of L.A. traffic have me good and freaked, so I arrive more than half an hour early. When Stewart shows up, on time to the minute, I'm being given a tour of a men's room filled with Marilyn Monroe tchotchkes; two dogs, both named Lola; and torn-out pictures of Jesus by Ruscha's brother, Paul. Stewart calls my cell to tell me she's outside. I open the door.

The girl on the other side might have made an eerily convincing young Joan Jett—says the real Joan, "Kristen studied me. Watched me talk, sing, breathe, just be. It got to the point where the two of us stood together and people couldn't tell us apart"—but it's a young Elvis Presley she's a dead ringer for: same almond-shape eyes (her vivid blue-green ones were dulled to a mud brown for Twilight), outlined in black, the lids heavy, hooded; same complexion, an undead shade of white, and without a mark, as poreless as marble; same mouth, narrow but full, made to sneer. She's rock 'n' roll skinny in tight jeans, scuffed Vans, a V-neck T-shirt, a pair of sunglasses dangling from the collar, hair long and tangled and dyed a brassy red, the roots dark. The look, pure Southern California street-punk guttersnipe, is very anti-glamour-puss. But she can downplay her natural assets only so much. Do I even need to tell you that she's very, very pretty? And though now 24, she could pass for much younger—a kid, fresh out of high school.

Stewart and I shake hands, and I introduce her around. Her manner is bashful, skittish, but she also seems eager to connect. Not just with Ruscha, who entered the room at almost the exact moment she did, but with Paul and Ruscha's assistant, Susan, and both dogs. With me, as well. Ruscha leads us into the body of the studio, which is enormous, originally built by Howard Hughes to manufacture airplane engines. At 76, he's still handsome, lean and suntanned, with a thick head of gray hair and lady-killer blue eyes. (His past girlfriends have included actress Samantha Eggar and model Lauren Hutton.) He looks less like an artist than like an old-time star of Hollywood westerns—Gary Cooper, maybe—only paint-spattered. Sounds like a western star too, not using many words when he talks, the words he does use coming out in a soft Oklahoma drawl. An ex-squeeze once called him "the king of shit-kicker cool." The title still fits.

The rapport between Ruscha and Stewart is natural and instant. He knows she appeared in Walter Salles' adaptation of On the Road, playing Marylou, Dean Moriarty's "beautiful little sharp chick," not a day over sweet 16, first seen naked, save for a pair of white cotton undies, rolling the perfect joint. He brings out a fine-arts edition of Kerouac's novel—one of Stewart's favorites—that he created a few years ago, photographs illustrating the text. As he turns the pages, Stewart calls out the names of the objects and places pictured: now-defunct brands of beer and automobiles, a pack of filterless cigarettes—"We smoked so many of those on the shoot we thought we were going to die!"—a plate of apple pie à la mode, so-lonesome-I-could-cry stretches of Arizona highway, Mexican whorehouses. She does this not in a show-offy way but with the pleasure of recognition, because she's seeing something that moves or excites her.

After Ruscha closes On the Road, he and Stewart continue to shoot the breeze, pushing remarks easily back and forth. They're bonding over a mutual love of light leaks in photos when I'm forced to break in because of a 12:15 lunch reservation and a promise I made to Stewart's publicist not to be too much of a little piggy with her time. Ruscha pulls out two copies of his book Porch Crop, inscribes one to her, one to me, and, cowboy gracious, walks us to the door.

Stewart and I take her black Mini Cooper, actually her mom's, to a restaurant a few blocks away. Before we walk inside, though, she ducks into a little nook/alleyway for a cigarette, which she smokes nervous-fast. Once we're at the hostess's station, I understand her momentary spasm of anxiety. Her head is bowed, posture turtled—she's practically willing herself into invisibility—and still people's eyes are drawn to her like iron filings to a magnet. Everybody stares. I mean, everybody. Even the people who look like they're not staring are staring. It's at that moment I realize—re-realize, I should say, since I knew it before meeting her but forgot after, so low-key does she seem, so unassuming, so, well, normal—just how major league a celebrity she is. Realize also that she must live much of her life at the mercy of strangers. For example, if just one of our fellow patrons decides to blow her cover by calling a news outlet (hey, this is L.A., people here probably have the scandal rags on speed dial) or tweeting that Oh Em Gee KStew is @ Akasha on Culver Blvd!!!, we'd have to go. Go hungry too.

The hostess leads us to a discreet table at the restaurant's rear. A waiter drops off menus and water. Stewart takes the chair facing the wall, giving her back to the room. Once it's clear we're alone and settled and no one's going to bug us, she visibly relaxes, pushing her hair out of her face and releasing the breath she must have been holding since we stepped through the doors.

For a minute or two we discuss the extreme weirdness of being her.

"So, basically, you can never look at people," I say.

"I'm obsessed with that. I'm always like, I can't look. Literally, most times, I would be staring at these girls [tilts her head to indicate which ones], but I haven't even glanced over there."

"Can't risk eye contact with strangers, right?"

"Right. Because then you're letting them in. But at the same time, you're like, What, I don't want to let anyone in? And, honestly, I'm super real with people. Incredibly. If someone's really cool and nice and just wants to talk, I will fucking hang out and chat all day."

The waiter returns, and Stewart opens her menu, quickly starts scanning the options.

While she's busy doing that, I'm going to address the big knock on her: that she doesn't like being famous or that she doesn't like being famous enough or that she's a little snot ingrate because she's insufficiently appreciative of the fame we, the public, mensches that we are, have bestowed upon her. As best I can tell, she gets this rep because there are times she doesn't say "Cheese" for the cameras. My sense of Stewart is that she's a naturally shy person, so she occasionally shrinks from the attention she provokes, and a naturally honest person, so she can't turn it on in an instant. And, okay, maybe she's a naturally rebellious person, too. And rebel spirit is in short supply in Hollywood. True rebel spirit, I mean, not just the trappings of it. There are plenty of starlets shticking badass—acquiring tattoos that can be covered with makeup, piercings that can be removed before shooting, substance addictions that are also conducive to weight loss. These girls, who show up at any red-carpet event that'll have them, flashing every capped tooth in their collagen-puffed mouths, are, at bottom, eager to please, are, at bottom, cowardly. They wouldn't dream of ever telling Mr. DeMille to take his close-up and shove it. My guess is that Stewart doesn't always play nice with the media because she knows the price for playing nice is too high. You give the media what it wants, and it takes and takes until you've lost yourself entirely, have become a smiley-faced, hollow-eyed nonentity—soulless, gutless, harmless. Better to stay defiant, keep your self-respect.

Stewart atones for her earlier cigarette with a kale salad. I copycat her order. The waiter takes away our menus, and we start the interview proper, getting the David Copperfield stuff out of the way first. Stewart is a local girl, born and raised in the San Fernando Valley. Her mom and dad are both in the show-business business: mom a script supervisor, dad a stage manager and TV producer. Stewart, at a very young age, decided to become an actor, not out of a desire for attention but for a job. "I wanted to go to work with [my parents] and have something to do," she says. "And the only thing you can do as a kid is be an actor. I saw kids on set, and I was like, What's that about? Why are they allowed to be here?" Her family background gave her a view of the industry that was brisk, practical, totally un-starry-eyed, and she's maintained it. Tim Blake Nelson, who directed her in the soon-to-be-released Anesthesia, marvels at her "blue-collar ethos."

Success came lickety-split. At nine, she landed the tomboy role in Rose Troche's The Safety of Objects (2001). At 10, she landed the tomboy role in David Fincher's Panic Room (2002). That she'd be a natural as Jodie Foster's daughter is a no-brainer, the two actresses matching up not just physically but temperamentally. ("Kristen was such a special, interesting, idiosyncratic child," Foster recalls.) Stewart would have to wait all the way till her eighteenth birthday for Twilight and superstardom, though when she signed on to the movie she thought, and with good reason, that it was an indie—mostly no-name cast, directed by Catherine Hardwicke, then best known for the ultra-low-budget Thirteen (2003).

"When did you realize how big Twilight was going to be?" I ask.

"The day the movie came out there was a picture of me—in the New York Post, I think. I was sitting on my front porch, smoking a pipe with my ex-boyfriend and dog. And I was like, Oh shit, well, I have to be aware of that."

She admits she found the sudden fame hard to handle: "I hadn't carved out my spot, and people hadn't gotten used to me yet. It was really fucking hard. I didn't interview well. I was really nervous. People fucking didn't respond that well."

In the past couple years, it's been back to the smaller-scale, more intimate projects Stewart was doing before and during the Twilight saga, with Snow White and the Huntsman as the notable exception. This souped-up, rock-'em-sock-'em retelling of the classic fairy tale enchanted audiences, if not critics, and helped make Stewart the richest of them all. (Forbes named her the highest-paid actress of 2012.)

(...)

Foster must've been gazing into her crystal ball. Stewart managed to hold it together, at least publicly, didn't break down or crack up, and at last the press got bored or lost interest—moved on, in any case. And she seems to have channeled whatever anger or upset she was feeling into her work. She has two movies coming out later this year, Peter Sattler's Camp X-Ray, about the bond that develops between a guard (Stewart) and a detainee (Payman Maadi) at Guantánamo, and Olivier Assayas' Clouds of Sils Maria, about an aging star (Juliette Binoche) and her devoted—too devoted, perhaps?—personal assistant (Stewart), both of which have been knocking them dead at festivals.

I ask Stewart who she's dating these days. Are she and Pattinson secretly back together? Or is she seeing Nicholas Hoult, Hollywood's young hunk du jour? Or has close friend Alicia Cargile become more than that? (In just the past 48 hours I've read gossip items suggesting all three possibilities.) It's none of my beeswax, of course, except that asking none-of-my-beeswax questions is part of my job description. Stewart's polite about it—certainly more polite than I deserve—but lets me know that her private life is precisely that, a stance I find personally admirable if professionally frustrating. She is, however, willing to discuss in abstract terms how a private life is even possible for somebody like her: "I just have to be really conscious. It takes a little bit of the impulsive nature of life out of the equation, but I—"

Stewart's interrupted by a text-message buzz. While she deals with it, I'm going to deal with the other big knock on her: that she has no dramatic range, is the same in every movie, a one-trick pony, basically. And though it's undeniable that the characters she embodies tend to resemble one another—intelligent but nonverbal, troubled, a little withdrawn—they're not identical. Stewart herself is aware of her limitations: "Some people try to do that thing where you craft a character. I cannot be anyone other than who I am. If I can't empathize with something [my character] does, it's a problem. And sometimes I've had directors be like, It's not you, Kristen, it's the character. And I'm like, That's the laziest thing you can possibly say to me. It is me. It's definitely me." My feeling is that Stewart's limitations are, in fact, her strengths. As a performer, she's deceptively simple, so natural is her style, so unforced. To play someone with a personality and consciousness totally unlike her own would be, in her mind, false. Says Jesse Eisenberg, "When we made Adventureland, [Kristen] would cut takes because she felt she was being inauthentic. She was 17!" Often what Stewart's doing appears plain and straight-ahead but is actually nuanced and complex, each of her roles a subtle variation on a common theme: herself. She's an American—Made in California, like the title of that famous Ed Ruscha piece—a West Coaster with a West Coaster's instinctive modesty and hatred of pretension and cool, courtly grace. If she can't make it look easy, she doesn't want to do it at all. Just because she makes it look easy, though, doesn't mean it is, and just because she doesn't put on the airs of an artiste doesn't mean she isn't one. You never see her acting, proof of how very good an actress she is.

Stewart sends off her text, and we keep the conversation going for a few more minutes. Our plates have long since been cleared, though, and she's sipping at the dregs of her coffee, me of my tea. I signal for the check, and we head outside. I sense she wants to smoke but is reluctant to light up because we're walking next to each other and I'm visibly pregnant. Once we say our goodbyes, she reaches for her keys, and I return to the restaurant to ask the hostess to call me a cab. As I wait, I look out the window. There's Stewart, slouched against the hood of her mom's Mini Cooper, squinting into the sun, a cigarette dangling from her lips. After taking a final drag, she lets the flaming butt fall to the pavement and swings her body through the driver's-side door. She starts up the car and enters the heavy flow of traffic on Culver without a pause or hitch. The princess of shit-kicker cool.

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento